Can we trust the Bible #2: Is the Bible true?

Is the Bible True?

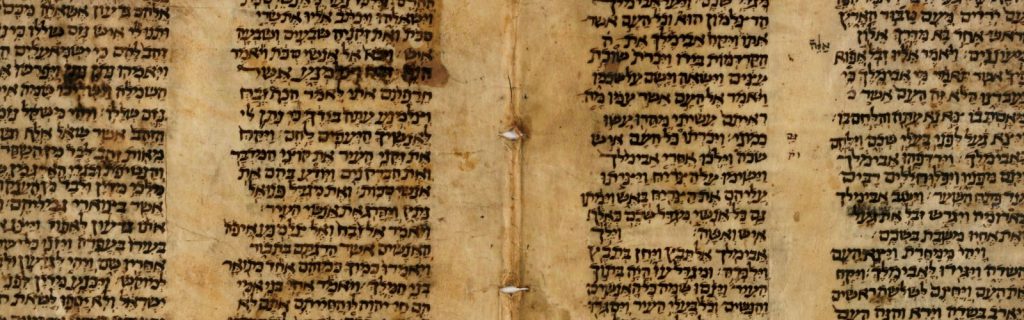

In the first part of this series, we looked at whether the Bible has changed through the ages, and we saw that through the insights offered by the academic discipline of textual criticism, we can be confident that the Bible books we have today are almost certainly identical to the books the first century church had.

Now we turn to the more fundamental question – is what was originally written true? And that’s quite a tricky question to answer because although the Bible is telling one big story in its 66 books, those books each contain hundreds of statements, written in many different writing styles, and it’s impossible to verify that all are true. Let me give you an example: There’s a romantic poetry book called Song of Songs, in which a girl’s nose is compared to the tower of Lebanon. As we don’t have a photo of the nose and the tower, how can we ever know if that is true (or whether the girl needed counselling to get over it)?

So what I’m going to do is focus in on one part of the Bible – the gospels – and explore whether they are reliable. So let’s put Matthew, Mark, Luke and John in the dock and cross-examine them.

First we’ll hit them with the “Forrest Gump” gaffe test. Why Forrest Gump? Well in the film the hero receives a letter from the computer manufacturer Apple dated Sept 23 1975. Sadly, Apple wasn’t founded until April 1976. So are there any major geographical or historical gaffes like that in the gospels? No – or at least none that are overwhelming problems.

From a geographical standpoint, the locations the gospels describe are all real, and the journeys the gospels describe are all possible. The historical figures referenced – people like Caesar Augustus, Pontius Pilate and Herod the Great – were all in power at the right times. And whilst the events of the gospels were too provincial to merit a mention by the Roman historians, the crucifixion of Jesus is mentioned by the Jewish historian Josephus.

There has however been some debate about the precise date of the census that Luke links with the timing of Jesus’ birth, but that’s most likely a problem with our ignorance of Roman censuses, rather than with Luke’s fact-checking. Archaeologist Sir William Ramsay sums the situation up well when he says,

You may press the words of Luke in a degree beyond any other historian’s and they stand the keenest scrutiny and the hardest treatment.”

So the gospel accounts fit with the history of the period, but that doesn’t mean they are true. In Hollywood language, could they just be myths “based on true events”? The problem with this argument is that the myths and legends of the ancient near east, and indeed the Greek and Roman world, all have a distinctive writing style, which the literature experts know how to spot. The countless minute details recorded in the gospels are a dead giveaway that they aren’t myths, but instead collections of eye-witness accounts. CS Lewis, who as well as writing marvellous children’s stories, was also Professor of English Literature at both Oxford and Cambridge universities, said either the gospels are eye-witness accounts or,

else some unknown writer in the second century, without known predecessors or successors, suddenly anticipated the whole technique of modern, novelistic, realistic, narrative.”

Next, let’s consider whether our eye-witnesses might have had a motive to invent a myth. Let’s ask, what did the gospel writers gain by writing, and by continuing to insist it was true? Most people who invent myths do it to gain money, sex or power; but the gospel writers got nothing but persecution, torture and death. It’s hard to imagine why they would go to their deaths insisting something they knew to be false, was true.

So far so good. I’ve argued that the gospels are historically plausible eye-witness accounts and that their writers didn’t have any plausible reason to deceive us. But that still doesn’t prove that the ideas Jesus puts across in the gospels about who he is and why he’s come are true – and if I’m honest, there are no clever words I can write in my final paragraph that will do that.

All I can do is invite you to explore for yourself what Jesus said about himself to see if it makes sense of the world and of your life. Most modern people encounter Jesus not through his own words, but through the filtered environment of the school classroom, or through documentaries and other people’s books. But the way to really encounter him is by reading one (or more) of the gospels in a modern translation. When people do that in a reflective and thoughtful way they often find themselves captivated by the sheer magnificence of Jesus. I know this from my own experience, and from the experience of countless others who have met him through reading the gospels for themselves. And when that happens, the question of whether what Jesus says is true is swiftly transformed into “What am I going to do about what Jesus says?”

If reading a gospel isn’t something you fancy dong on your own, on May 8th, I’m starting another Christianity Explored course, which will introduce Jesus through the gospel of Mark. To book in, visit our website at www.hopechurchfamily.org/courses

To find out more:

- Read, Can I really trust the Bible – a book by Barry Cooper.

- For an academic treatment of the question of the historical reliability of the gospels, you can do worse than start with the Wikipedia article about this topic.

- For more on the accuracy of Luke’s date for Jesus’ birth read “Is Luke wrong about the time of Jesus’ birth?”

First published in the Bridge Magazine, April 2017