Can we trust the Bible #3: Is the Bible full of contradictions?

Does the Bible contradict itself?

We all love to catch a politician contradicting themselves – but what about the Bible? Does it contradict itself, as you’ll sometimes hear people say, and if that’s the case, how can we trust anything it says?

Personally when people say “The Bible is full of contradictions” to me, I like to ask them which contradiction they have in mind – because often they don’t actually know of any – they just heard or read it somewhere.

But when they do name a contradiction, that’s when the fun starts, because as someone who is committed to the trustworthiness of the Bible, contradiction is a big issue to me!

Thankfully most of the possible contradictions people identify fall into one of five categories and turn out not to be contradiction at all. Let’s take a look at them. The first is:

1) The Typo.

The Old Testament book 2Chronicles (36:9) says Jehoiachin became king of Judah when he was 8 years old. But the other account we have of his reign, in 2Kings (24:8) says he was 18. Which is true?

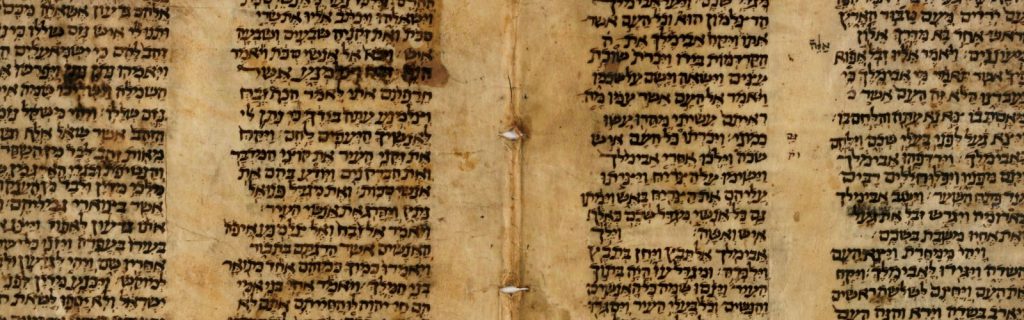

This contradiction is likely to be a result of what we call “scribal error.” That is – at some point an error crept into the copying process of either 2Chronicles or 2Kings. We looked at these “errors” in the article about whether the Bible we have today has changed since it was originally written.

Broadly speaking we said: No – the Bible has not changed – certainly not in any of its major details or doctrines. But occasionally it’s hard to deny a discrepancy has crept in, and most good modern translations highlight them.

Another category of contradiction is:

2) Intentional

Proverbs 26.4-5, says,

Do not answer a fool according to his folly, or you yourself will be just like him. Answer a fool according to his folly, or he will be wise in his own eyes.”

That seems to suggest that wise old King Solomon was so dumb that he put two contradictory proverbs next to each other. But far more likely is that he’s trying to teach us something about how to use his proverbs. You see proverbs never pretend to be one-size fits all solutions. True wisdom is knowing which one works when!

These “intentional contradictions” raise an important issue: that we can’t call something in the Bible a contradiction, until we’ve properly understood the type of literature we’re reading. So for example, we don’t read the erotic love poetry of Song of Solomon in the same way we read the Nativity Story (and we certainly wouldn’t want to get them muddled up in a school assembly!)

Here’s another kind of contradiction:

3) Ignoring the bigger story!

In the Old Testament, sin is forgiven by offering animal sacrifice. In the New Testament, sin is forgiven by the sacrifice of Jesus on the Cross. Which is right?

Answer: Both – but at different times in the bigger story of God’s dealing with his people! Some contradictions only exist because we haven’t thought about how they fit into the bigger story – the unifying plot that runs all through the Bible – from the opening chapters of Genesis to the final chapters of Revelation with the death and resurrection of Jesus as the hinge-point.

A related type of contradiction is:

4) Failure to understand the context

This isn’t so much a failure to grasp the bigger story, as a failure to grasp the more immediate story. So for example, Ecclesiastes 7:29 says,

God made man upright”

whereas Psalm 51:5 says,

Behold I was brought forth in iniquity.”

That looks like a contradiction, until you explore the context of the two verses. In the first the writer is talking about Adam and Eve and God’s original, perfect creation. In the second, the writer is talking about his own sinfulness. And because the two verses are speaking of something utterly different, they are not in contradiction.

A final type of contradiction is caused by:

5) Misinterpretation.

For example, when Jesus entered Jerusalem, Matthew 21:7 says he had two donkeys, but Mark 11:7 says he had one. Surely this is a contradiction.

At face value, it does look one – though it could just be a typo. But what’s more likely is that we’re misinterpreting the words to see contradiction where there is none. For example, are these two statements contradictory:

At John’s funeral we sang Abide with Me”,

and,

We sang Abide with me and The Lord’s my Shepherd at John’s funeral”?

No – they just emphasise different things – and most likely that Matthew and Mark are doing something similar.

So, is the Bible full of contradictions? No! Scholars have spent years analysing them, and most of them can be attributed to one of these five broad types.

If you’ve got a contradiction in mind that’s really bugging you, why not email me at barry@hopechurchfamily.org and let’s see if we can’t find a way though it!

To find out more:

- Read, Can I really trust the Bible – a book by Barry Cooper.

- Read: The Big Book of Bible Difficulties, by Norman L Geisler and Thomas Howe

First published in the Bridge Magazine, May 2017